The Power of Simplicity (Mungerisms Expanded #1)

0. TL;DR: don’t get fancy, get good at the basics.

Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett teach an important lesson: don’t get fancy, get good at the basics.

And I concur: The power of the basics is often underestimated.

Yet, it doesn’t take a 180+ IQ to do things right. It’s just that people are not methodical enough to make sure they always do the basics. People are in a rush. They cut corners, and hide it with superficial sophistication.

But nailing the basics only takes a checklist of To-Dos and Not-To-Dos, then duly going through them each time you have to make a decision.

Airplane pilots best embody this mentality: they have a checklist and they need to tick each box before being allowed to depart. This is how they avoid getting lenient, this is how they avoid a crash.

Unfortunately, except pilots, few commit to this level of diligence. It’s as if because people know the basics are simple, they assume basics are not valuable enough to try to nail them.

The intellectual shortcut goes like: basics = simple = easy = not valuable enough. But basics are powerful, valuable, and hard. They’re like this resource with infinite potential, from which most of us will only scratch the superficial layer.

Read further down to learn how Munger & Buffett elaborate on mastering the basics.

1. Introduction

This is my first article of a series: “Mungerisms Expanded”

I recently finished reading Charlie Munger’s “Poor Charlie's Almanack”, after reading Warren Buffet's biography “The Snowball” 4 years ago.

In our world, few strangers can be said to be your friend. Generally, if a stranger talks with you, it is in order to serve their interests, either by selling you a good (salespersons), or an idea (politicians).

However, among this selfish crowd, stand some singular characters who really intend to elevate their fellow humans.

I count myself lucky to be contemporary of two of these unique fellas: Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. Warren, the world’s richest financier, Chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, needs no introduction. But still only a few insiders have heard about Charlie.

If Charlie is mainly known as Berkshire Hathaway’s Vice Chairman, Warren’s best friend and alter ego, I believe this usual presentation doesn’t do him justice.

So let me introduce him to you: Charlie is a polymath, an intellectual prodigy who has crafted his own multidisciplinary system to analyze the world, phenomena and humans, in order to make decisions. His financial track record and 10-figures net worth speak for themselves.

Now, do you know what’s the best part of this?

Both Warren and Charlie, inspired by Ben Franklin’s life, have embraced a preacher’s ethos: they share, often, and for free, to whomever may listen to them, the philosophy and habits that made them happy in life, as well as successful in business.

Charlie, although less fond of spotlights than Warren, has publicly shared his technics and principles throughout the years during speeches for different organizations. And he eventually compiled his speeches in a single book: “Poor Charlie’s almanack”, a subtle reference to Ben Franklin’s “Poor Richard’s Almanack”.

I honestly believe “Poor Charlie’s Almanack” to be the best book one may read during their life. It is packed with so much wisdom, it’s actually hard to wrap one’s head around all the ideas Charlie introduces in his speeches, and fully grasp their power when duly applied.

Having read and meditated on Charlie’s ideas for the past few months, I have decided to offer my own take on their meanings, and how one may apply them in one’s own life.

This will be my series of articles “Mungerisms Expanded”.

Today is my first issue of the series, titled “Power of simplicity”.

2. Take a simple idea, and take it seriously

Charlie once said:

Take a simple idea, and take it seriously.

What did he mean by that?

Well, let me illustrate with another episode.

Someone asked Charlie once why more people hadn’t copied Berkshire Hathaway’s approach to investing. In his usual blunt style, Charlie replied

“More investors don’t copy our model because our model is too simple [...]. Most people believe you can’t be an expert if it’s too simple.” Charlie Munger

So the point I will try to make in this article is that most people neglect the fundamentals because they believe them to be too basic, and instead go and elaborate fancy constructs, intellectual scaffoldings, adding extra layers of complexity to their reasoning.

The problem is, these extra layers will often occult the fundamental, basic requirements one idea must verify in order to be successful.

This is how fancy analyses can result in bad decisions: people lose fundamentals from sight. They lack common sense.

All that being said, let me take a few illustrating examples of people or organizations neglecting the fundamentals, thus falling into the “fancy construct trap”:

3. Case 1: “fancy” restaurant: Café Bohème, Paris

I live in Paris in a very dynamic district. A few years ago, a new bar/restaurant opened in that area, place Edgar Quinet. That restaurant is called “Café Bohème”, and here’s a photo of its terrace.

You’re probably thinking “oh, this place looks charming, I’d love to have a drink there with friends.” Why did you think that? Because aesthetically, this restaurant is attractive. It means they used a good marketing trick to attract customers inside.

Good.

But that’s merely lipstick, and it does a whole difference whether it is applied on a beauty or on a pig. Because as I’ve experienced it time and time again, once you sit at this restaurant, you get one of the worst possible customer service possible.

It will take a good 10 minutes before the waiter brings you the menu, 10 more before they take your order, and another 15 if you’re lucky and they eventually bring you the drink/food you actually ordered – which happens to be bland. Needless to say, the waiters are in a rush and unpleasant with you during the whole thing. So you’d eat, wait some more to get the check, then ask for the credit card machine, and you’d leave.

What happened there? The restaurant had a charming front, therefore attracting a lot of clients.

But once seated, it couldn’t deliver on a restaurant’s value proposition. The restaurant’s owner focused the efforts on appearances, adding the extra layer of beautiful design, but lost the basics from sight: people go to restaurants to have pleasant people serve them good food.

Therefore, after a couple of times going through this exact process, I have sworn to never go back to that mediocre restaurant.

Now, let’s take the opposite example: Jiro Ono’s sushi restaurant in Tokyo, Japan.

4. Case 2: “basic” restaurant: Sukiyabashi Jiro, Tokyo

Here’s a photo of Jiro’s restaurant:

So, wanna go there? Chances are: it seems so basic that you’re meh about the whole thing.

Now, what if I tell you that Jiro’s restaurant is renowned for being the world’s best sushi restaurant? It was the first sushi restaurant to get 3 Michelin stars, and a Netflix documentary was even made to tell Jiro’s story of what it means to be a true craftsman who honors one’s craft.

You may be left wondering how such a successful Chef can be working in such a modest store? Well, the answer is simple: Jiro has focused all his efforts, for more than 70 years of sushi-crafting, solely on perfecting his art: making the world’s best sushi ever.

So much so that Jiro didn’t pay attention to all the less essential marketing-y aspects of his business. His approach has been: let’s become the best sushi chef ever, and then let my work speak for itself. Or what is referred to as “word-of-mouth” or “organic” acquisition, i.e. a way of attracting new customers without having to invest neither time nor money in marketing campaigns. The idea is: you’re so good at what you do that people rush to your door and beg you to take their money.

This approach was well synthesized by YCombinator when they said:

“Growth is the result of a great product, not the precursor.” YCombinator

It means the first step to building a great business is to offer a delighting “value proposition”.

And Jiro’s so exceptional at the fundamentals – offering great sushi – that the world’s most illustrious men & women, like Barrack Obama back to when he was POTUS, have taken reservations 6 months in advance to enjoy a 35 minutes meal in Jiro’s modest 10-seat, 20 sq.-foot, restaurant located in a subway station.

My point here is to show a living example of Charlie’s “take a simple idea and take it seriously.”

In Jiro’s case, he took the simple idea of crafting the world’s best sushi ever, and dedicated his whole life to it. That’s it. Sushi. Only sushi. Not sushi + salad + meatballs + ramen. Just sushi.

To become the best, Jiro didn’t try to offer the most complete menu possible. No, he didn’t add extra layers of complexity. He reduced his scope to 1 single dish, namely sushi, and kept at it for 70 years.

It seems ridiculous. What is sushi? A slice of raw fish on top of a ball of rice, add a little soy sauce and wasabi here and there? How hard can it be? Does it really take 70 years of monk-like dedication to make good sushi?

“I betcha’ I can make decent sushi in just a few hours by following a Youtube tutorial” some of you may think.

Well, think again. Sushi sure is one of the simplest dishes there is. But does simple mean easy? No. Simple is hard. People underestimate simple products or concepts because they are easy to half-ass in a superficial way. It may take 3 hours to learn how to make average sushi, but it takes a lifetime of dedication to craft an extraordinary one.

And where most people or businesses fail, is that they neglect the power there is in simple ideas. They barely scratch the surface and exploit 1% of the potential of simple ideas, and then go half-ass the next thing on their checklist, believing they have “ticked the box”. These people will never unlock the full potential that lies within simple ideas. Heck, they’re not even aware such a potential exists.

5. Generalization: master the fundamentals

Back to Charlie’s quote:

Take a simple idea, and take it seriously.

What is the application of Charlie’s quote to product design? It is to execute extraordinarily well on a narrowed-down number of basic features.

As Paul Buchheit puts it in his great article:

“If your product is good, it does not need to be great”. Paul Bulchheit

In other words, your product does not need to offer all the possible features, but it does need to focus on the biggest pain points and solve them extremely well.

This brings us to the most essential takeaway of my article: the power of simplicity.

I want to emphasize the “simple” part of the “take a simple idea and take it seriously.”.

Charlie’s message is to be very serious with simple ideas. Not to disregard them because they seem too basic, but to focus on them, obsessively work on them, and to squeeze every ounce of juice they can offer.

It is no coincidence if the greatest makers have time and time again praised simplicity: Leonardo da Vinci, Jiro Ono, Steve Jobs, …

These geniuses took products, stripped them off their unessential parts, and then uncompromisingly focused on building the best possible version of each of the components or features of their products. They didn’t try to do everything well. They kept the most essential parts and focused on making them great.

I would say their genius is threefold:

A. Philosophical: on a higher-level, they understand the superiority of simplicity, and abide by its demanding rules.

B. Exploratory: while investigating people’s needs, they have the uncommon ability to identify and distinguish what is essential from what is not. They understand the deepest desires and motivations of the human psyche.

C. Applicative: once they have isolated the core problems they want to solve, they relentlessly and uncompromisingly work on designing/crafting the best possible solution to each sub-problem.

Combining these three flavors of genius in a single person is no trifle. This is why you so rarely see new Jiros or Steve Jobs.

But those who A. understand the power of simplicity, B. explore the world’s problems to isolate essential sub-problems, and C. have the focus and discipline to deliver extraordinary versions of simple components, will find uncommon success in their life.

It is a mindset that can be trained, refined and acquired. I invite all of you who’ve reached this far in my article to strive for simplicity and to make it the paramount standard of all your actions.

6. How to unlock the power of simplicity?

“The only way to win is to work, work, work, and hope to get a few insights.” Charlie Munger

Let’s say that at this point you have become convinced of the importance of being serious about simple ideas. Good. Now, how do you go on and actually unlock the full power of simplicity?

You work incredibly hard for a long time and focus to get the fundamentals right.

That’s it. Working hard. Patience. Dedication to one’s craft. Learning to appreciate the process more than the proceeds. It’s the same good old formula.

Why does it work? Because by practicing the same actions over and over again while trying to improve, you progressively peel off the superficial layers of understanding, and you get access to the core of the idea, where most of its power lies. You start to perceive nuances you didn’t even know existed before.

Inwardly, you become able to break down the “making” process into a finite number of atomic steps. And you then realize there is no such thing as an “atomic” step: you realize each step, each movement, each action, can be infinitely broken down into tinier sub-steps. Dizziness generally ensues. You are awe-struck by the beauty of Creation.

And it is at this turning point that, consciously or not, you make the following life-defining choice:

Do I want to face each new threshold one by one, am I ready to keep pushing to improve in infinitely smaller margins?

Becoming a craftsman means embracing this lifestyle, it means committing to this quest. All the others become average jacks.

This may sound romantic and esoteric, but it’s not. Let me illustrate with Jiro’s example.

If you were to become an apprentice at Jiro Ono’s restaurant tomorrow, you know what he would have you do? Cook rice. That’s it. For the first few couple of years, the only thing you’d be allowed to do would be to cook rice. Nothing else. Why? Because rice is the essential component of sushi, and Jiro would want you to get intimately familiar with it.

Only after a few years of rice-focusing would you be allowed to enter the next stages of sushi making: choosing the best raw materials (rice, fish, soy sauce, rice vinegar, wasabi, …), choosing the best instruments (knife, rice cooker, …), mastering to the perfection every move it requires to make sushi, choosing the right dimensions for your fish, choosing the right dimensions for your rice, adding just the right quantity of soy sauce and wasabi, etc.

If this seems like an endless process, it’s because it is.

This is what it takes to become the Jiro Ono, the Charlie Munger, or the Steve Jobs of your craft.

So now, are you ready to dedicate your life to the quest for simplicity?

7. The End

I hope this first article of my series “Mungerisms Expanded” will have shed sufficient light on great concepts and persons to convince you of the importance of simplicity.

I can assure you that, on a personal level, I am committed to the quest of mastering the fundamentals and building the most simple, elegant experiences.

If you’ve liked this article, and want to react, feel free to reach out to me or comment: I’m always looking for stimulating conversations and challenging feedback!!

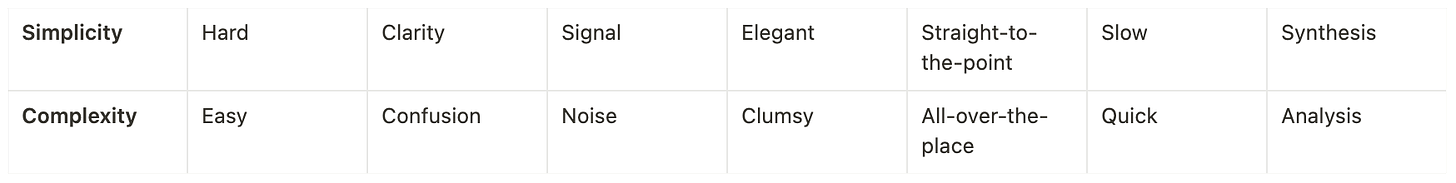

I’ll leave you with a bonus table I have concocted to remind me of important distinctions: simple is hard.

How to read this table?

Lines are equivalences: simplicity = hard = clarity = signal = …

Columns are opposites: simplicity ≠ complexity; hard ≠ easy; clarity ≠ confusion; …